November 18, 2022

The dismemberment of ownership of proprietary rights is without doubt an essential estate planning technique. In Belgium, the principle is simple: full ownership of an item of heritage is understood as “full powers” over that asset, i.e. the right to both enjoy it and receive the fruits thereof and dispose of it (gift, alienation, loan, etc.).

Full ownership can thus be subdivided into two other rights in rem:

- Usufruct: the right to “use the fruits” or enjoy the proceeds of an asset whose ownership right belongs to a third party

- Bare ownership: the ownership right over the asset, its patrimonial value

The subject of a usufruct may be one movable asset or a set of movable assets. It can be established by the owner of the movable asset(s) for a fixed or indefinite period. Finally, a usufruct automatically lapses upon the death of the usufructuary, and the full ownership of the asset reverts to the bare owner.

The new property law (which entered into force on 1 September 2021) extended the prerogatives of usufructuaries to some extent, while introducing the notion of legal accretion applying to a common usufruct. These developments have naturally led OneLife to develop new estate planning techniques.

The proposed solution will depend on a number of factors, including the origin of the dismemberment of ownership, whether it existed prior to the investment or rather was created in order to / while subscribing to a Branch 23 life insurance policy.

- Summary of the structure of a Branch 23 life insurance policy

The investor/policyholder of a life insurance policy enjoys rights to the policy in return for the payment of a premium (in full ownership) to the insurance company[1]. All these rights (including, but not limited to, the rights of total/partial surrender, switch, and beneficiary appointment/revocation) constitute for the policyholder a guarantee of control over the underlying assets invested.

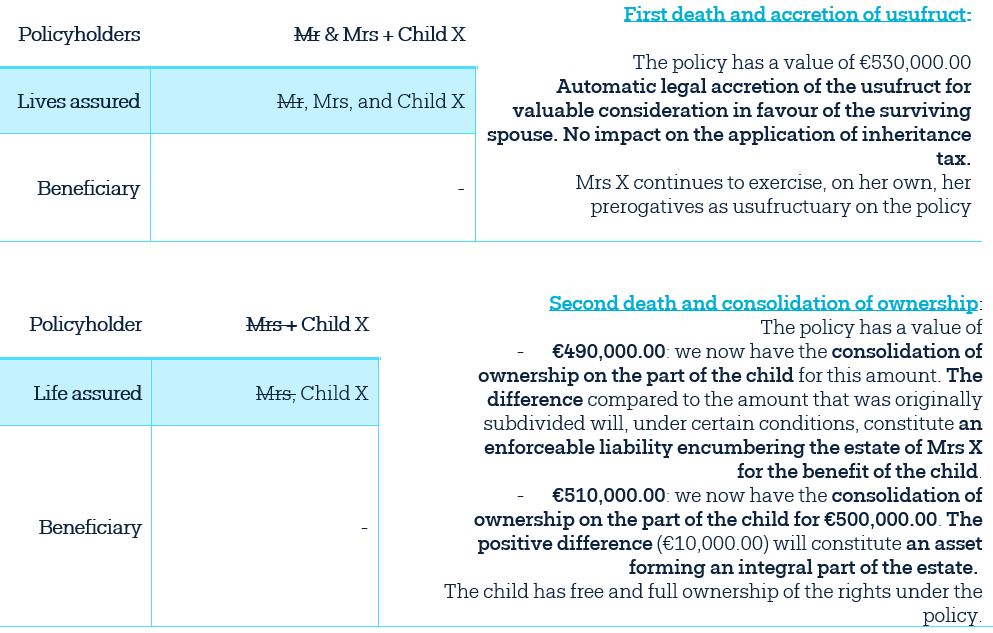

Since the full ownership must be designated in the policy, both the usufructuary and the bare owner will be designated together in the policy, contractually creating a joint ownership between them. Customarily, the policyholders will also be represented as lives assured under the policy. This means that the death of the usufructuary will not give rise a claim under the policy, but rather that the full ownership of the rights under the still-active policy will then devolve to the surviving policyholder, i.e. the bare owner. At this stage, and for lack of utility, the policyholder would not have designated a beneficiary upon taking out the policy in our example.

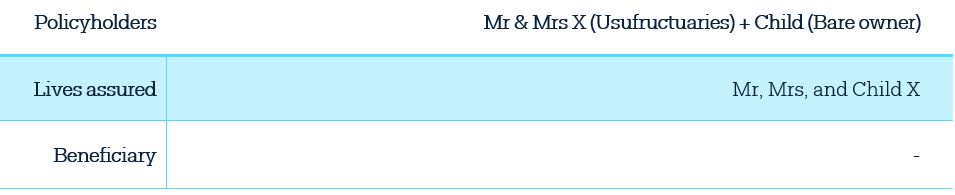

Take, for example, Mr and Mrs X, married under the regime of community of property and having a child together who they wish to name as a beneficiary in the context of their estate planning. They hold a savings account amounting to €500,000.00 and gift the bare ownership of this sum to their child. They decide to register the reduced gift tax on this transaction. They then take out a Branch 23 life insurance policy, structured as follows:

2. Joint ownership in a life insurance policy: Is less actually more?

While the Insurance Act (Articles 169 et seq.) mentions that the rights of the policyholder are strictly personal and cannot be exercised by others, the presence of several policyholders changes the way these rights are exercised. In fact, a plurality of policyholders necessarily implies joint exercise of the rights in order to ensure complete enforceability against the contracting insurance company.

The question of “who can do what” in a situation where the proprietary rights are subject to a dismemberment of ownership is then of crucial importance.

The new Book 3 of the Belgian Civil Code comes to the rescue, clearly determining the regime applicable to the usufructuar(y)(ies).

The first comment that comes to mind is undoubtedly the inclusion, in Article 3.141, paragraph 4 of the Act, of the legal accretion of usufruct in favour of the surviving usufructuary in the case of a common or joint usufruct. While the intention of the parties was to implement vertical estate planning (leaving the estate to their child), we see in this accretion an opportunity to protect the surviving usufructuary (in our example, the surviving spouse), and therefore achieve horizontal planning.

Since the life insurance policyholder holds a claim, we will turn to the section dealing with usufruct on monies owing:

- Under Article 3.164 of the Belgian Civil Code, a usufructuary can legally (and on his/her own) claim the payment of monies owing, while the bare owner may only do so with the usufructuary’s agreement. It follows that the usufructuary, unlike the bare owner, can proceed to policy surrenders on his/her own.

- In addition, Article 3.148 of the Belgian Civil Code states that the usufructuary may sell the encumbered asset outside the limits of his/her prerogatives if such sale corresponds to the destiny of the property as contractually stipulated between the parties.

- Finally, in the case of permitted alienation (under Article 3.148), the Act references the obligation of restitution contained in Article 3.159.

Mr and Mrs X having expressed the wish to retain control over management and information in the conventional organisation of the dismemberment of ownership of proprietary rights, their child, as bare owner, will have signed over to them a general management mandate and a transfer of the right to information. Mr and Mrs X will therefore be able to administer the policy and proceed to surrenders on their own, whereas their child will need their agreement to do so.

3. Alienation / surrender / disposal of capital: So anything goes?

While the new property law grants the usufructuary a certain flexibility (which is highly similar to a “quasi-usufruct”), we must remain aware of the limits imposed by the spirit of the law:

- Usufructuar(y)(ies) are not subject to any restrictions with respect to policy surrenders relating to the (contractually stipulated) fruits of the policy

- Capital surrenders will be assessed in light of the relevant legal and contractual provisions. Unlike non-essential expenditure, necessary and useful expenditure to maintain the lifestyle (and human dignity) of the usufructuar(y)(ies) are not contrary to the spirit of the law.

4. What about taxes?

Briefly:

- The dismemberment of ownership may have existed prior to the investment or be created while subscribing to a Branch 23 life insurance policy

- The usufructuary and the bare owner are designated together in the policy, contractually creating a joint ownership between them

- The policyholders are also represented as lives insured under the policy. There are no designated beneficiaries

- The legal accretion of usufruct in favour of the surviving usufructuary is definitely an achievement in terms of horizontal planning and is foreseen by the pure application of the law

- The usufructuary can alone proceed to policy surrenders, unlike the bare owner, who can do so only with the usufructuary’s agreement

- Attention point: although the usufructuary is not subject to any restrictions with respect to surrenders relating to the fruits of the policy, capital surrenders are subject to the limits enacted in the relevant legal provisions.

![]() Nicolas MILOS

Nicolas MILOS

Senior Wealth Planner, OneLife

Want to know more? Contact our teams.

[1] Insurance Act of 4 April 2014, published 30 April 2014