The following people all have something in common.

Can you spot what it is?

- Mr Martin, a French established business owner, has a savings policy through his company and would like to arrange a bank loan for the company.

- Mr and Mrs Peeters, a retired couple from Belgium, have an endowment policy, of which their children are the beneficiaries, and they are looking for a loan to buy the house of their dreams without having to surrender their policy.

- Mr Larsson, a doctor from Sweden, has an endowment policy, of which his wife and children are the beneficiaries, providing unrivalled protection of Luxembourg life insurance policies offered by OneLife. He wishes to pledge his policy as security to help one of his children to buy a flat.

As you have no doubt noticed, all these people wish to use their endowment or savings policy as security for a loan, bank or otherwise, for themselves, their company or one of their close relatives!

So, why and how do you pledge a life insurance policy as security?

Is it possible to pledge the policy’s underlying assets as security, or must the people in the above examples surrender their policies?

What are the mechanisms for pledging an endowment or savings policy as security?

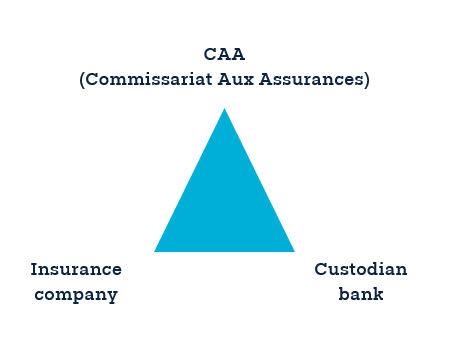

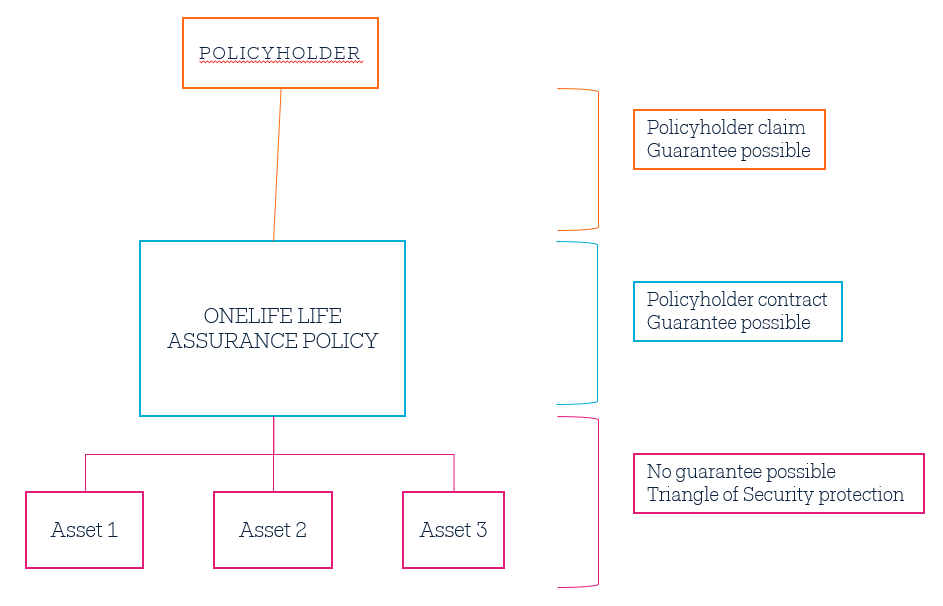

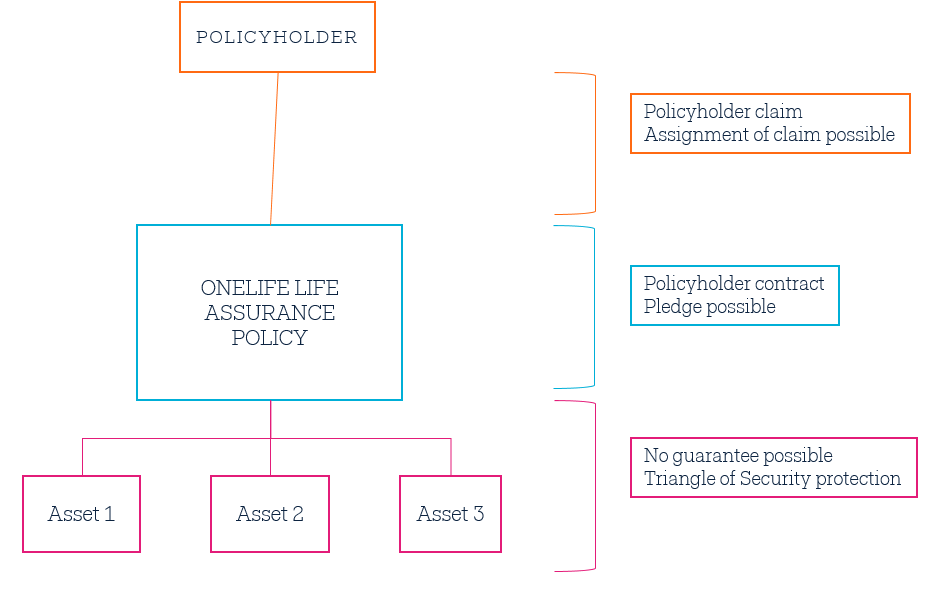

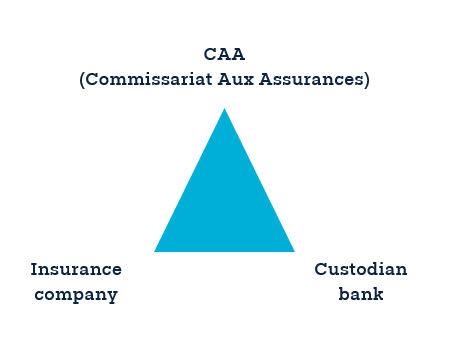

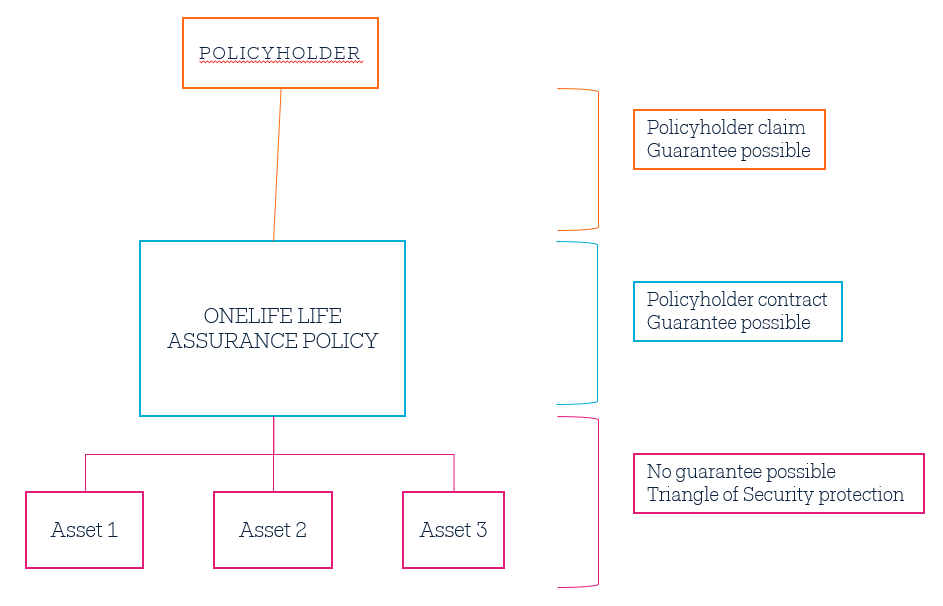

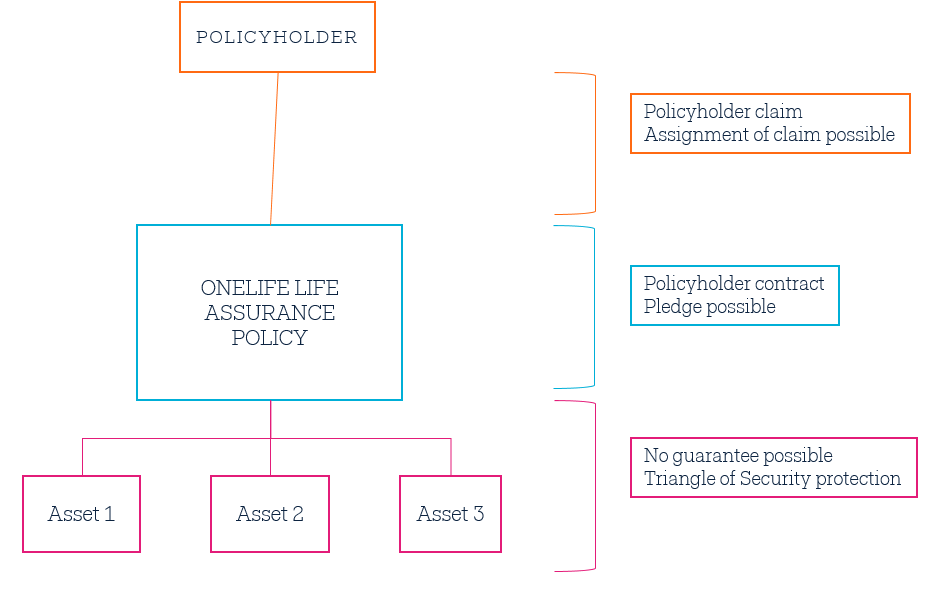

First, it is important to note that, due to the Triangle of Security, there can be no lien of whatever kind on the underlying assets of a life insurance policy. Any lien must either be on the policy itself (where an endorsement to the policy is required) or on the claim held by the policyholder with regard to the insurance company (where an endorsement to the insurance policy is not required).

Thanks to the Triangle of Security, the assets held within a Luxembourg endowment or savings policy are separated from the insurance company’s other assets. By virtue of article 3 of the tripartite deposit agreement between the insurer, custodian bank and Insurance Commission, neither the bank nor the insurer can accept privileges or liens other than a super privilege on the underlying assets! => Here!

Extract from article 3 of the deposit agreement template produced by the Insurance Commission:

“the assets deposited […] must be separated from the depositor’s other commitments and assets with the credit institution […] and may not be offset with the latter. There can be no privileges or liens other than those provided for by article 118 of the law [super privilege] on the assets deposited.

Notwithstanding any provision to the contrary contained in the general terms and conditions or other contractual documentation between the credit institution and the depositor, the credit institution recognises this separation and prohibition of offsetting. “

Consequently, there can only be a lien at a level above the assets deposited, that is to say, on the policyholder’s policy or claim:

The acceptable mechanisms for attaching a guarantee are as follows:

- Assignment of rights

- Designation of a beneficiary

- Pledging the life insurance policy as collateral

- Assignment of the life insurance policy

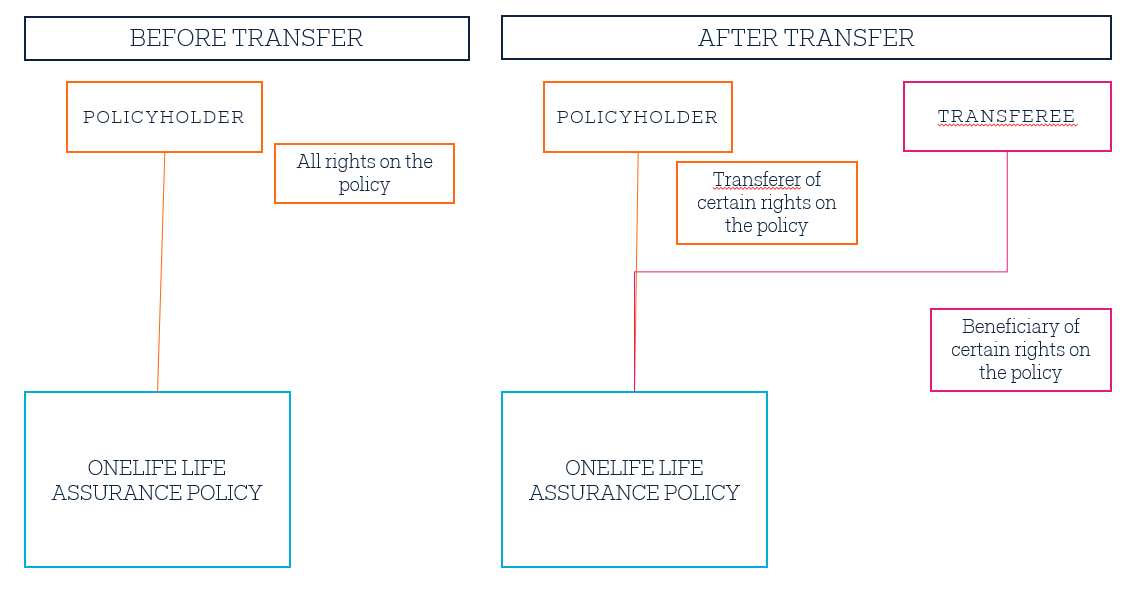

1. Assignment of rights for endowment or savings policies

Commonly used in Belgium, the assignment of rights is governed by articles 183 and 184 of the Law of 4 April 2014 on insurance:

Art. 183. The rights under insurance policies may be assigned in whole or in part by the policyholder. This assignment right cannot be exercised either by the policyholder’s spouse or creditors.

In the event that the benefit is accepted, the assignment right can only be exercised if the beneficiary agrees.

Form

Art. 184. All or part of the rights under the policy can only be assigned if an endorsement is signed by the assignor, assignee and insurer.

However, the policyholder may stipulate in the policy that on his death, all or part of his rights will be assigned to the person designated to that effect.

The assignment of rights is similarly governed by article 118 of the Luxembourg law on insurance policies, which is based on Belgian law.

In French law, the assignment of rights is governed by article 1216 of the French Civil Code. However, French law prohibits the assignment of rights for endowment policies. Rights under savings policies can however be assigned in French law!

The person wishing to assign his rights is known as the assignor. He can assign his rights to a third party, the assignee, free of charge (donation) or for a consideration (in exchange for a service, a bank loan for example) in the following 3 ways:

- assignment of all the rights under the insurance policy and transfer of this policy to the assignee, for example his children or, in consideration of a loan, the lending bank;

- assignment of all the rights under the insurance policy, without the policy being transferred;

- a partial transfer of the rights under the policy.

The rights under the policy may be assigned in whole or in part. For example, the following rights may be specifically assigned:

- the right to change the investment allocation among the investments linked to the policy;

- the right to designate the beneficiary;

- the right to surrender the policy;

- the right to pledge the policy;

- the right to information on an annual basis or from time to time.

In the event that a right is assigned to more than one person, the assigned right will be exercised jointly by the assignees.

However, this assignment of rights means that the assignor automatically loses the assigned rights, which can be difficult to accept for some policyholders. Likewise, the beneficiary must expressly approve the assignment of rights.

In practice, the partial or total assignment of rights, with or without transfer of title of the policy, is very common in Belgium but seldom or never used in other markets (such as France for example).

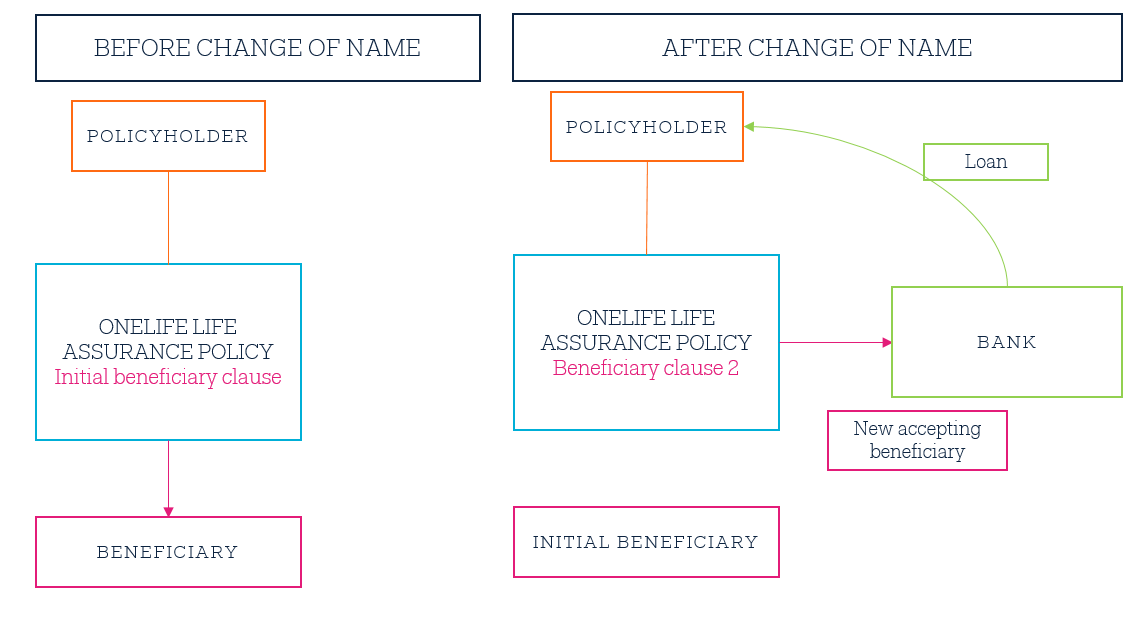

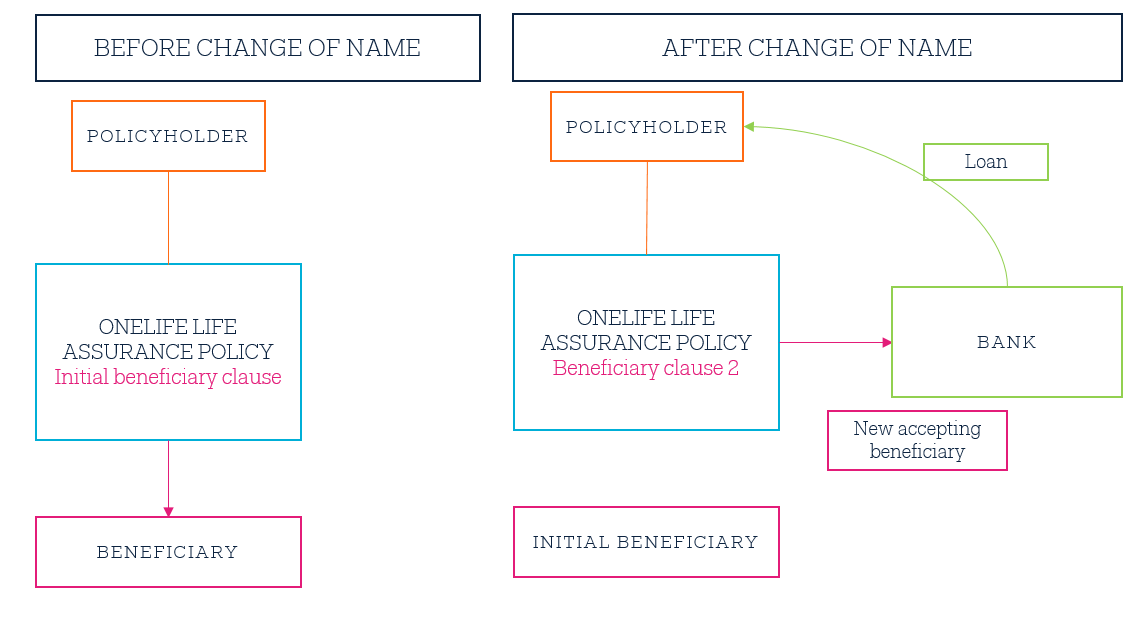

2. Designation of beneficiary as a guarantee

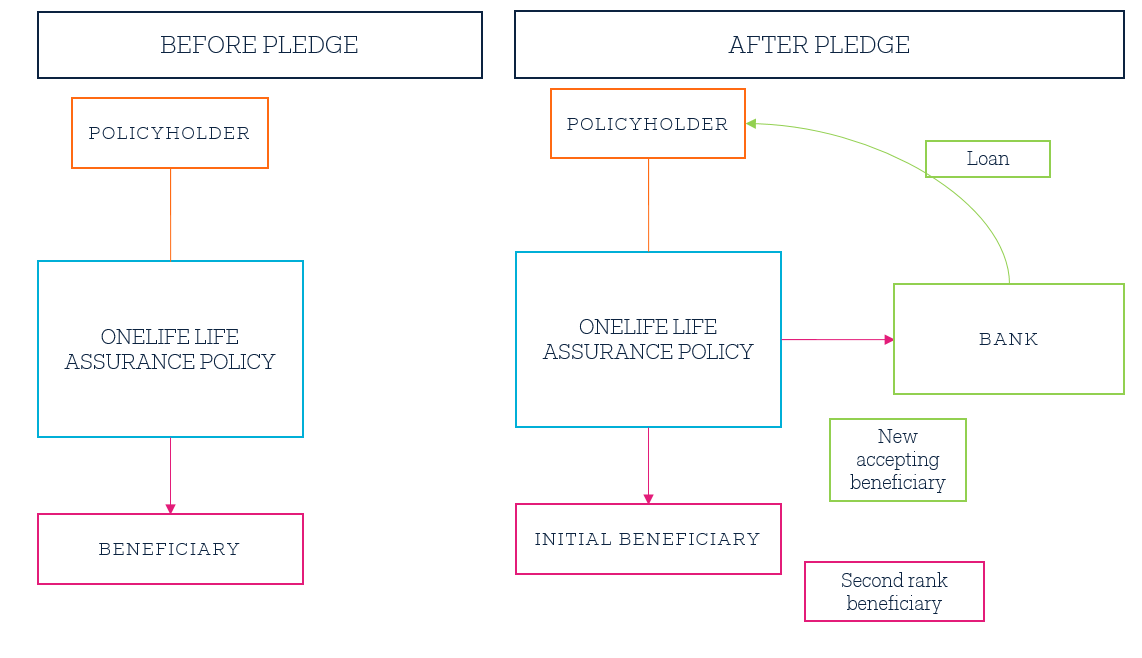

A third party can be designated as first-ranking beneficiary of the insurance policy as a guarantee for a debt owed by the policyholder to a bank or any other third party.

By way of illustration: Mr and Mrs Peeters would like a bank loan in order to buy the house of their dreams in Tuscany. Since the house is not located in the country where the bank is established, the bank demands a solid guarantee in addition to the standard repayments under the loan agreement.

Mr and Mrs Peeters are therefore going to designate the bank as first-ranking beneficiary of the life insurance policy as a guarantee for the loan to buy the house of their dreams. The bank is going to accept the benefit in order to secure its position and the claim pledged as collateral for the loan.

In practice, this mechanism requires the policyholder to designate the bank as accepting beneficiary and, therefore, the policyholder loses the right to designate a new beneficiary and must ask the accepting beneficiary’s agreement for any future transaction.

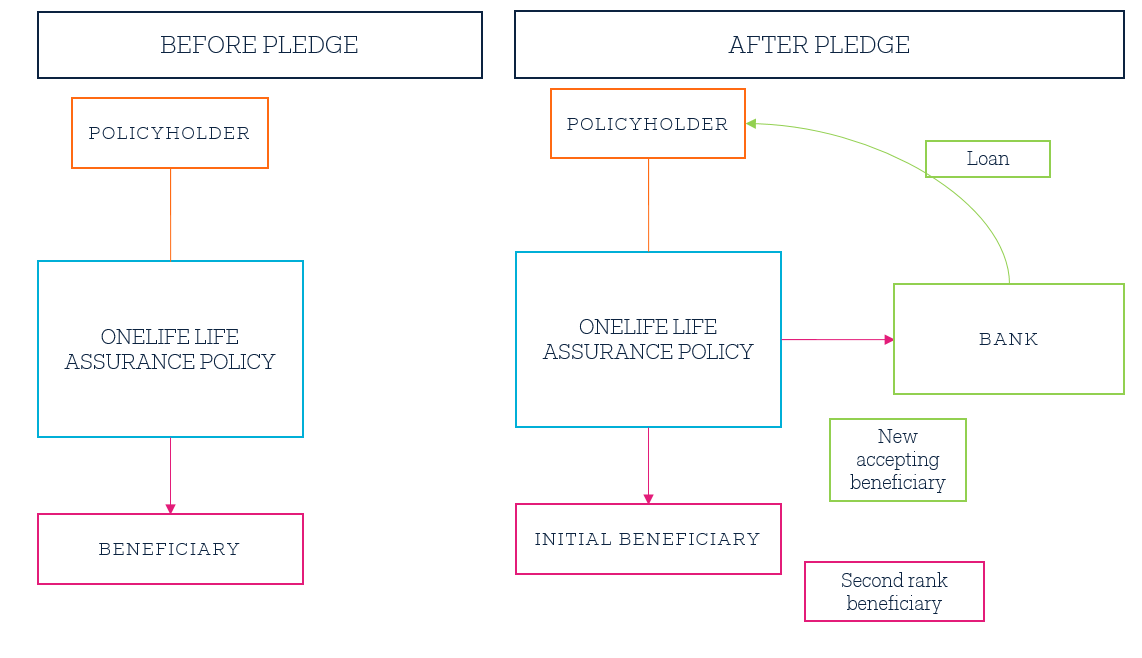

3. Nantissement of the insurance policy

Another possibility is nantissement, a mechanism used in France, which is equivalent to attaching a lien on the insurance policy. Nantissement is a type of pledge, that is to say, a charge on moveable property applied to an intangible asset, for example shares or a life insurance policy.

French law makes a distinction between nantissement and a pledge (gage), which, in French law, applies to tangible assets (property that a person can hold in their hands).

Nantissement is provided for in article 2355 of the French Civil Code and is defined as the contract by which the debtor gives possession of an intangible asset to its creditor as security for its debt.

By using nantissement, a debtor can grant a lien on its endowment or savings policy since the policy is an intangible asset (a contract representing a claim of the policyholder on the insurance company).

In Luxembourg as in Belgium, the term used is the term “pledge”, but the mechanism is the same, and an endorsement to the insurance policy signed by the insurer, policyholder and bank is required.

Articles 116 and 117 of the Luxembourg law of 27 July 1997 on insurance policies states that the right to pledge an insurance policy is a personal and exclusive right of the policyholder. However, in the event that the benefit is accepted, the prior consent of the beneficiary is required.

Moreover, the provisions of the Luxembourg law are based on Belgian law, including articles 181 and 182 of the Law of 4 April 2014, which states:

“Right to pledge the policy

Art. 181. The rights under the insurance policy may be pledged; they may be pledged only by the policyholder and not by his or her spouse or creditors.

In the event that the benefit is accepted, the pledge is subject to the beneficiary’s consent.

Form

Art. 182. A policy can only be pledged by means of an endorsement signed by the policyholder, the secured creditor and the insurer. “

Nantissement is a separate contract, but requires an endorsement to the insurance policy. The law that applies to nantissement is the same law that applies to the life insurance policy. In practice, nantissement is allowed, but it is less used than assignment of claim because it is subject to a specific regime governed by the law applying to the insurance policy.

Nantissement is therefore less flexible and gives less protection both for the policyholder and for the bank, in particular compared with the assignment of claim (described below), which is the most commonly used mechanism for pledging a life insurance policy as security. According to the law applying to the insurance policy itself, nantissement is subject to the legal, regulatory and jurisprudential regime applicable in the law of the policy.

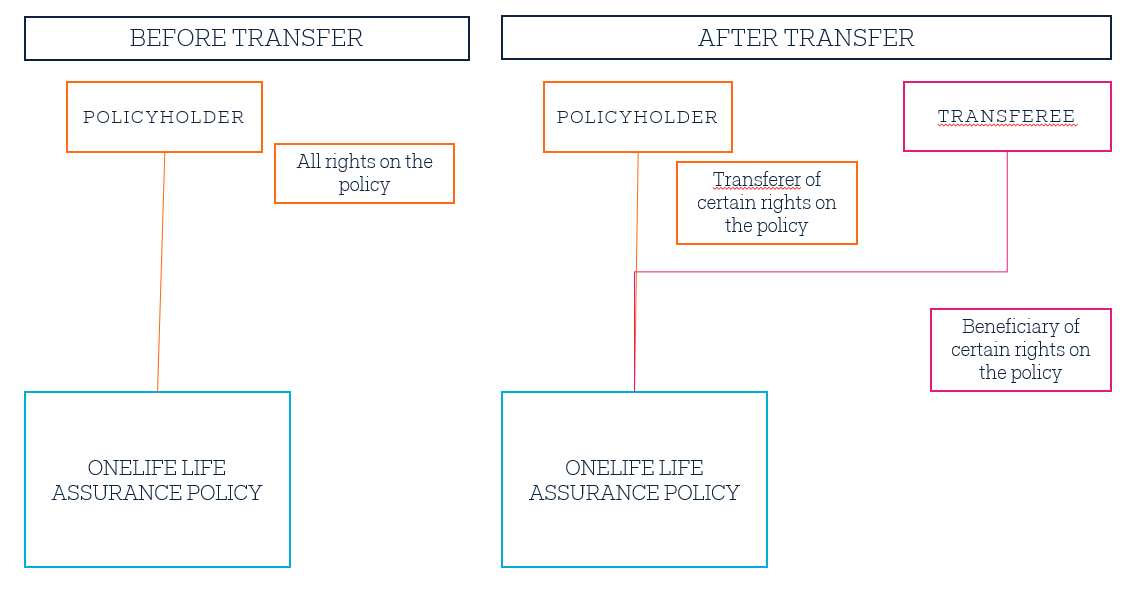

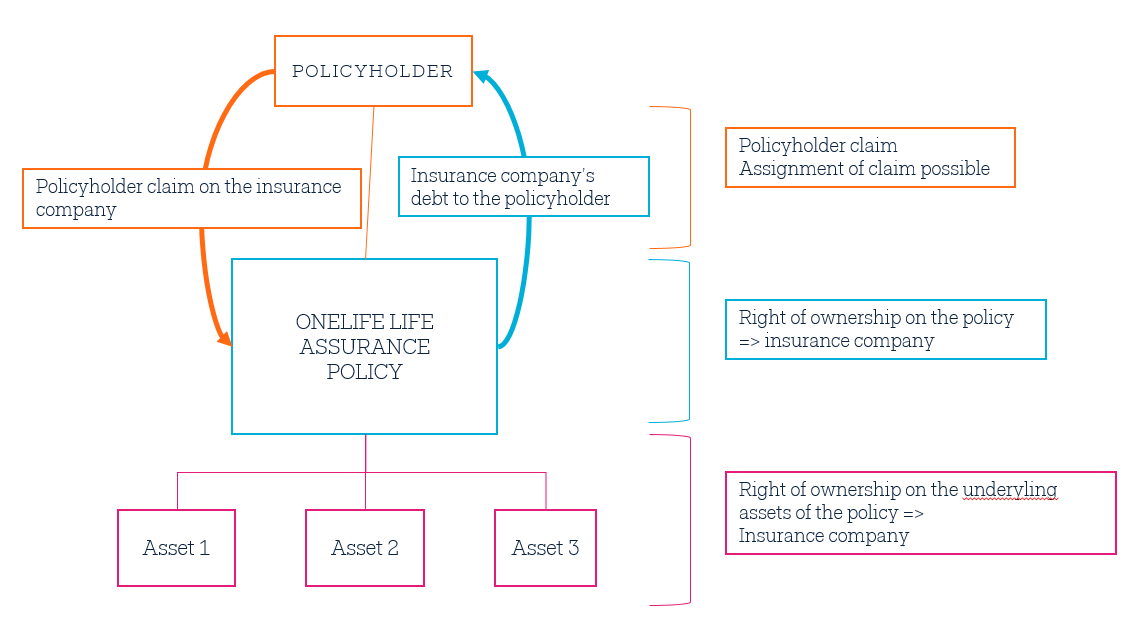

4. Assignment of claim

4. Assignment of claim

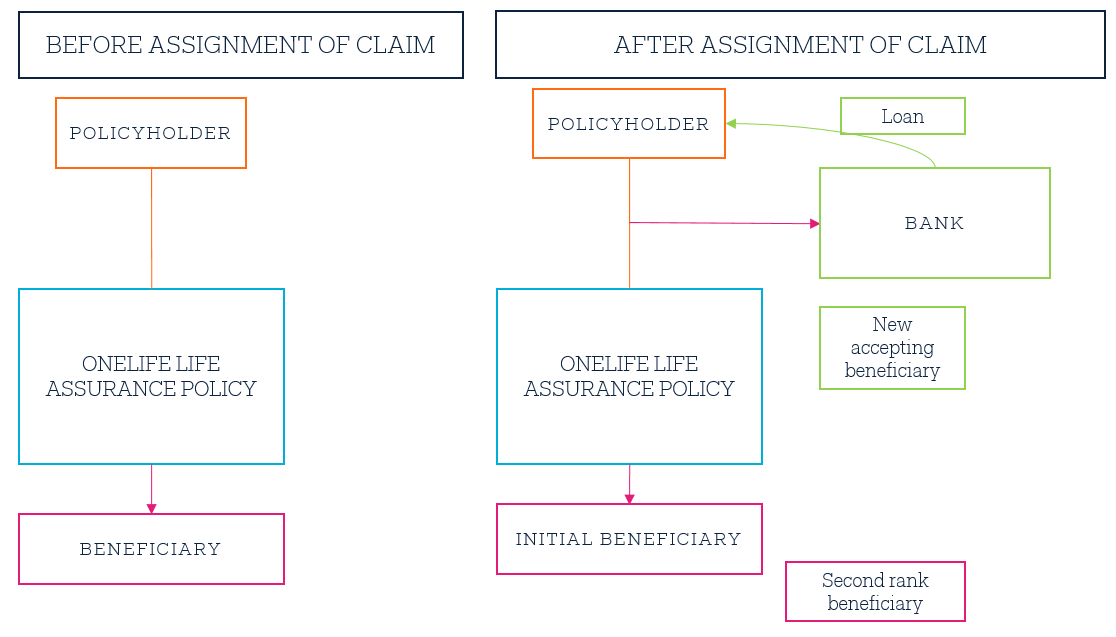

The term may appear obscure for the layperson, but assignment of claim is the mechanism of choice for pledging an endowment or savings policy as security.

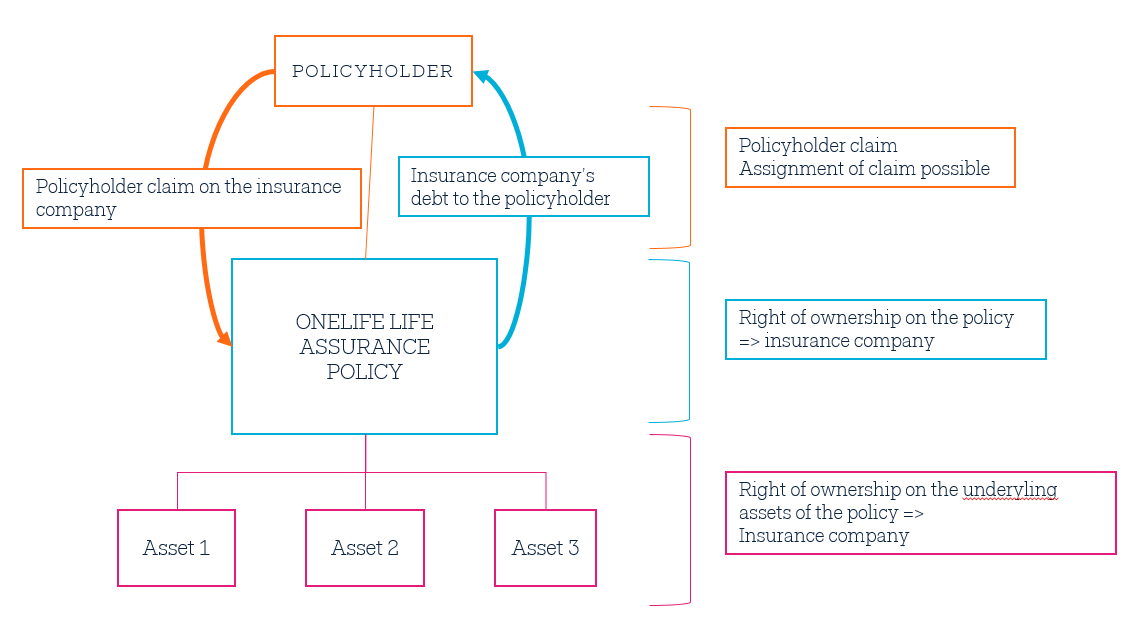

The policyholder has rights under the policy, and the first of these rights is not a right of ownership on the policy or assets (contrary to popular belief), but a right of claim, that is to say, the policyholder has the right to be paid the policy’s surrender value. The insurance company therefore has a debt it owes to the holder of the policy, and the assignment of claim operates at the level of the policyholder’s claim and not at the level of the policy itself, which is the case for nantissement.

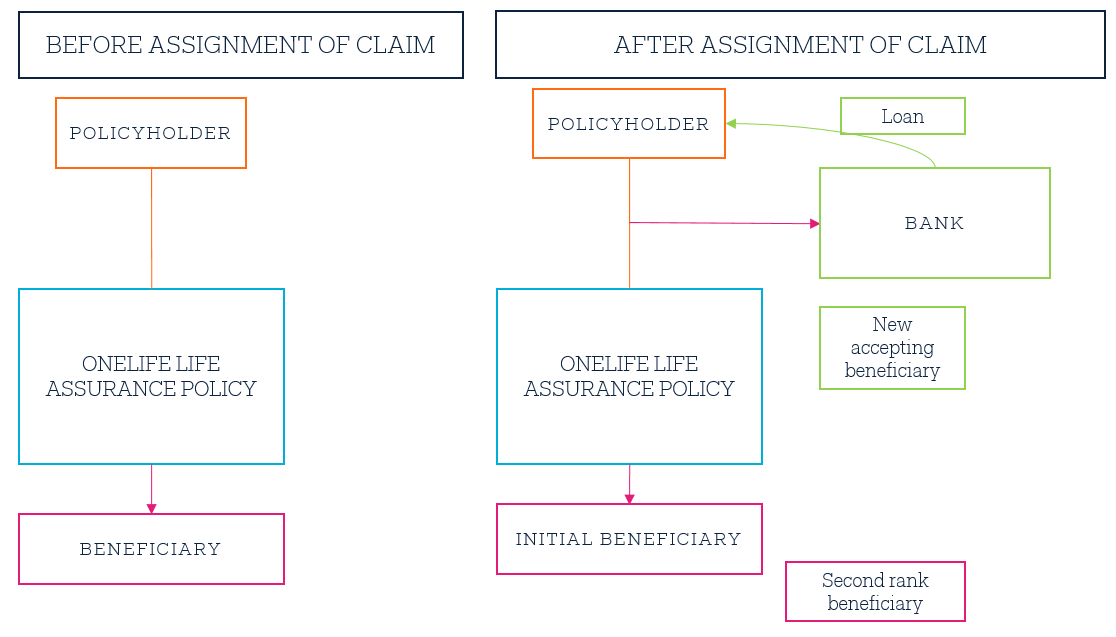

To summarise the situation of the policyholder and insurance company once the insurance policy has been effected:

The mechanism of the assignment of claim is provided for in article 1275 of the Luxembourg Civil Code:

“The assignment by which a debtor provides the creditor with another debtor, who has an obligation to the creditor, does not operate by novation unless the creditor expressly declares that he intends to discharge his debtor who made the assignment. “

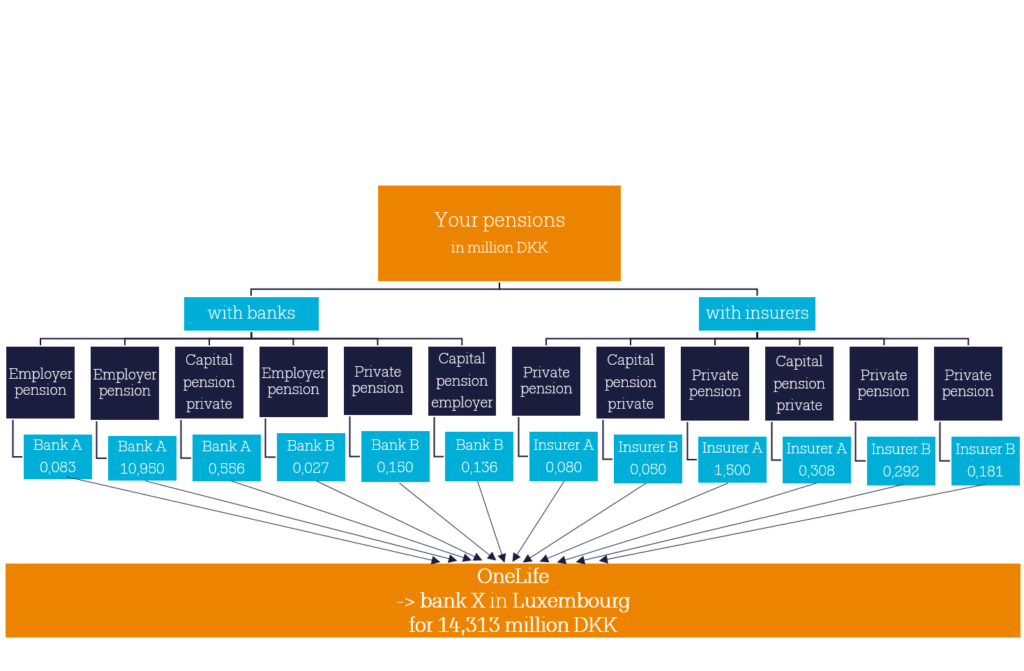

Through the mechanism of assignment of claim, the policyholder obliges the insurance company to repay the lender (usually the bank, but not always the case) in the event that the policyholder defaults. Therefore, the bank has a second debtor to call upon should the main debtor default.

Similarly, the debtor and assignor (policyholder) do not have to be the same person, and a person can assign its claim for a debt that has been contracted by another person.

For example, Mr Martin, the established business owner from France, may assign his claim on his personal policy for a debt contracted by his company. As for Mr Larsson, he may assign his claim on his policy as security for the debt contracted by his son to buy a flat without surrendering the policy.

Only if Mr Larsson’s son or Mr Martin’s company defaults may the bank collect on the guarantee and demand to surrender the policy in whole or in part, which in no event may the insurance company refuse because of the assignment contract – within the limit of the sums due by the debtor (that is to say Mr Martin’s company or son) and the surrender value of the life insurance policy.

Moreover, the assignment of claim does not require an endorsement to the life assurance policy, and it is very common for an assignment of claim under Luxembourg law to be used, which may cover all the existing and future debts of a given debtor.

Finally, the regime of assignment of claim is the most flexible and by far the most used in practice.

Once the debt has been repaid in full, the bank or third-party lender releases the assignment, and the policyholder regains the rights that were limited by the assignment. Therefore, designation of a beneficiary and nantissement (lien), but also assignment of claim, do not mean the policyholder loses its rights, contrary to the assignment of rights which, in order to be lifted, requires that the rights are assigned back to the policyholder.

Each of these methods for attaching a lien on a life insurance policy has its advantages and drawbacks. It is worth noting however that assignment of claim has the most flexible regime that is best suited to a large number of situations and does entail the policyholder losing his rights, but just a temporary limitation of those rights.

The tripartite assignment can be summarised as follows:

Want to know more? OneLife’s experts are here to help offer you and your clients’ wealth solutions.

Please speak to your OneLife contact, who will be pleased to help.

Jean-Nicolas GRANDHAYE, Corporate Counsel at OneLife

Jean-Nicolas GRANDHAYE, Corporate Counsel at OneLife

In Belgium, the purpose of civil law reform on succession and donations was to modernise the inheritance framework of the Civil Code, dating back to 1804. The principles of these reforms have been applicable since 1 September 2018 and have had a major impact on donations and debt being brought back into the estate in order to respect the equality between the heirs and the respect of their reserved share (minimum share made available to each heir by Law). This mechanism is the so-called hotchpot.

In Belgium, the purpose of civil law reform on succession and donations was to modernise the inheritance framework of the Civil Code, dating back to 1804. The principles of these reforms have been applicable since 1 September 2018 and have had a major impact on donations and debt being brought back into the estate in order to respect the equality between the heirs and the respect of their reserved share (minimum share made available to each heir by Law). This mechanism is the so-called hotchpot.

![]() Nicolas Milos

Nicolas Milos

4. Assignment of claim

4. Assignment of claim

1. Freedom to provide services

1. Freedom to provide services

1. The signature by France and Belgium of a Convention preventing double taxation of successions

1. The signature by France and Belgium of a Convention preventing double taxation of successions