Should I invest in real estate or life insurance products? The clock is ticking… but the dilemma no longer exists: you can do both!

Indeed, the question no longer matters, because the answer is simple: investing in real estate through your life insurance policy is the perfect solution!

Of course, just as you cannot physically carry your gold bars or your barrels of oil to your insurance company, neither can you contribute your house as a life insurance premium!

Well then, what can you do?

Let’s take a look at the investment opportunities and the legal and tax framework for investing in real estate through life insurance.

- Investment opportunities

Currently, faced with declining yields in fixed-income funds, investors like you are increasingly turning toward higher-performing investments with limited risk.

Why should you invest in real estate through your life insurance policy?

Whether you want to aim for higher returns, hold a safe and limited-risk asset, boost your savings, benefit from attractive taxation compared to direct ownership or hold an asset outside of your estate, there are many good reasons to invest in real estate through your life insurance policy!

For a limited investment, you can hold an asset that is both secure—because it is based on a diversified real estate portfolio of office buildings, nurseries, medical clinics, retirement facilities, etc. (which also frees you from management burdens like unpaid rents, a lack of tenants, property showings, etc.)—and mutualised, and which yields an average of 5% per year!

What real estate assets can you invest in?

You are probably familiar with the terms SCPI, OPCI, SIIC in France and SIR in Belgium. You may also invest in real estate through listed or unlisted real estate funds, or you may set up your private real estate portfolio within a company and hold its securities within your insurance policy.

As you can see, the possibilities are many and varied. We will focus here on describing the legal and tax framework for holding French SCPIs and OPCIs and Belgian SIRs within your life insurance policy.

- Legal and tax framework for investing in real estate through life insurance

Of all the real estate investment opportunities offered through life insurance, the most popular are investments in SCPIs, OPCIs and SIRs. Let’s take a look at them:

a. Sociétés Civiles de Placement Immobilier (SCPI)

Sociétés Civiles de Placement Immobilier (Private Real Estate Investment Fund) are companies whose sole purpose is the acquisition and management of a real estate portfolio for commercial or residential use.

Management is outsourced to an approved management company that is responsible for renting and maintaining the real estate assets.

The sums paid in by subscribers are destined for the purchase and management of the real estate assets.

In return for their contributions (the minimum unit price is €150), the company pays rents to subscribers in proportion to the subscribers’ contributions, less the costs related to the real estate portfolio (maintenance costs, rental management, various works, etc.).

Similar to a direct real estate investment, it allows investors to earn real estate income without the worries of rental management while enabling them to invest even with modest sums.

SCPIs can be closed-end or open-ended funds. Closed-end SCPIs issue new shares until their capital is fully subscribed, after which they are said to be closed, in contrast to open-ended SCPIs which continuously issue and cancel shares.

The SCPI is tax transparent, i.e., each investor is individually taxed on the company’s taxable income in proportion to the shares he or she holds.

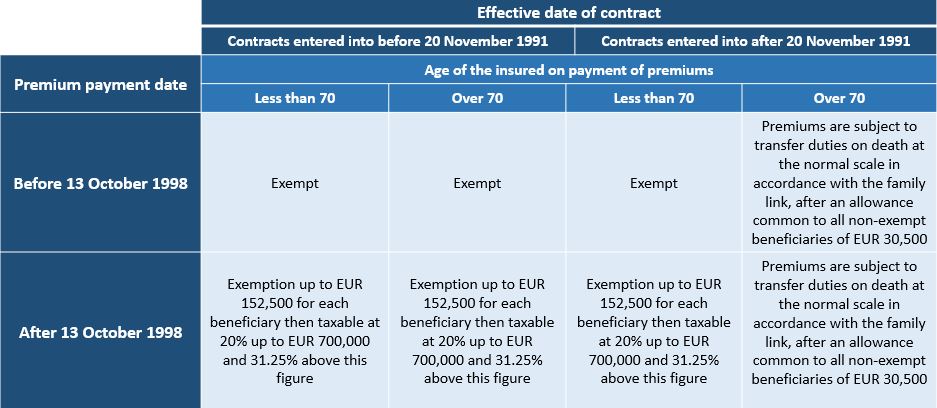

Income from French sources (rents and capital gains) generated by the SCPI held through a OneLife insurance policy is taxable at the corporate income tax rate in France of 33.33% (rate to be reduced to 28% in 2020, 26.5% in 2021 and 25% from 2022 onwards).

Capital gains on the sale of SCPI shares are also taxable in France at a 33.33% rate (aligned with the corporate income tax rate).

b. Organismes de Placements Collectifs Immobiliers (OPCI)

Organismes de Placements Collectifs Immobiliers (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Real Estate) are real estate funds which were originally created to replace SCPIs, but now coexist with them.

The purpose of OPCIs is to invest in, build, maintain and rent out real estate assets.They may also renovate the assets and resell them. In addition, the corporate purpose may include the management of financial securities and deposits.

Since the Macron Act of 2017, the French Monetary and Financial Code (CMF art L2014-34) has also allowed OPCIs to incidentally acquire furnishings, equipment and any other movable property allocated to the buildings held and necessary for their operation, use or exploitation.

There are several types of OPCIs depending on the investor’s profile, whether professional or retail, and level of risk: specialised OPCIs, OPCI umbrella funds, etc.

OPCIs aimed at professional investors (which benefits policyholders) are as follows:

– OPCIs established as a Société de Placement à Prépondérance Immobilière à Capital Variable (SPPICAV – Open-ended real estate investment companies)

– and those set up as a Fonds de Placement Immobilier (FPI – real-estate collective investment undertakings).

Both forms of OPCI have the same legal nature but their legal and tax frameworks differ.

SPPICAVs are constituted as a Société Anonyme (public limited company) or Société par Actions Simplifiée (simplified joint stock company) with variable capital. This means that the purchase of shares gives the subscriber ownership rights over the company, in proportion to the amount of his or her contribution, as well as voting rights at general shareholders’ meetings.

FPIs are not incorporated but are joint-ownerships.Investors hold units and not shares. They have no ownership interest in the FPI and have no right of control or decision-making.

The subscription of FPI shares is exempt from registration fees and property advertising tax.

The sale, redemption or distribution of OPCI units or shares, or distribution of FPI assets are exempt from registration fees and property registration tax with two exceptions provided for in Article 730 quinquies of the CGI: holding more than 10% of the OPCI for the individual acquirer or 20% for the legal entity acquirer entails registration fees of 5%.

SPPICAVs are vehicles exempt from corporate income tax, but subject, in particular, to the obligation to distribute their profits to their shareholders.

Income distributed by a SPPICAV is considered to be financial income (dividends) and its taxation depends on the shareholder’s status (legal entity or individual) and his or her place of residence.

Under French domestic law, dividends distributed to non-resident shareholders are generally subject to French withholding tax of 30%.

If held through a OneLife policy, the tax treaty between France and Luxembourg allows this rate to be reduced to 5% for dividend-receiving companies that hold at least 25% of the distributing company’s share capital and to 15% for lesser holdings.

However, under the new tax treaty between France and Luxembourg, which should come into force on 1 January 2019, these rates are likely to change. Dividends paid by an OPCI will be subject to a reduced withholding tax of 15% when the beneficiary company directly or indirectly holds less than 10% of the share capital of the distributing company and 30% if the holding is greater than 10%.

Capital gains on the sale of SPPICAV shares are taxable in France at a withholding rate of 33.33% (aligned with the corporate income tax rate).

As for the taxation of investments made by FPIs, see the taxation applicable to SCPIs (tax transparency).

c. Les Sociétés Immobilières Règlementées (SIR)

The legal framework for Sociétés Immobilières Règlementées (regulated real estate investment companies) is set out in the Belgian Act of May 12, 2014, which came into force on July 16, 2014. The SIR’s purpose is in particular to “make buildings available to users, whether directly or through a company in which it has an interest, and, as the case may be and within the limits provided for this purpose, to hold other types of “real estate assets“.

This type of company has commercial and operational activities but is not obligated to act in the interests of shareholders, because the collective public interest serves as the legal rationale for this corporate structure in Belgium.

A company whose actual managers can only be individuals, the SIR covers the entire real estate sector: from holding real estate (and thus ensuring its management, urban conformity, etc.) for the long-term, with the aim of making it available to users, to the construction or renovation of real estate assets. For this purpose, the SIR must carry out its own activities without delegating any responsibility to another legal entity. This presupposes a concrete “substance” in terms of operational teams.

Incorporated as a “société anonyme” (public limited company) or a “société en commandite par actions cotée en bourse” (publicly-traded limited partnership) with at least 30% of its shares traded on the market (i.e. with publicly held voting rights), the SIR is subject to the control of the Autorité des Services et Marchés Financiers (FSMA) and to strict rules regarding conflicts of interest.

The SIR may not, however, invest more than 20% of its assets in a single property complex, as its investments must be diversified. In exceptional cases, this limitation may nevertheless be waived, subject to a reasoned opinion from the FSMA.

The SIR is not subject to corporate income tax in Belgium under the express condition that it distributes at least 80% of its net income in the form of dividends.

Withholding tax on dividends is 30%. However, depending on the investment of the SIR concerned, a “reduced” withholding tax may apply. A case in point is the SIR investing in health care properties.

Where shares in a SIR are held through a OneLife insurance policy, the life insurance package allows the taxpayer to avoid any 30% withholding tax on income from movable property. Indeed, under the Double Taxation Treaty between Belgium and Luxembourg, the withholding tax on dividends may not exceed 10% or 15% in Belgium.

Moreover, investing in real estate through a life insurance policy allows the capital to grow by reinvesting the income received while benefiting from deferred taxation. In effect, taxation only takes place in the event of a partial or total redemption and according to the tax regime applicable to life insurance policies: the taxable capital gains on redemptions will be pro-rated according to the percentage of the capital redeemed.

Also, since 1 January 2018, assets held indirectly through a life insurance policy have been included in the taxable base for French property tax under the rules applicable to residents and non-residents.

Your professional advisor and OneLife experts are at your side to advise you on the best real estate investments to subscribe through your life insurance policy.

Onelife, it’s now, or whenever!

Authors:

Fanny PERPERE – Wealth Planner

Fanny PERPERE – Wealth Planner

Nicolas MILOS – Senior Wealth Planner

Nicolas MILOS – Senior Wealth Planner

Jean-Nicolas GRANDHAYE – Corporate Counsel

Jean-Nicolas GRANDHAYE – Corporate Counsel

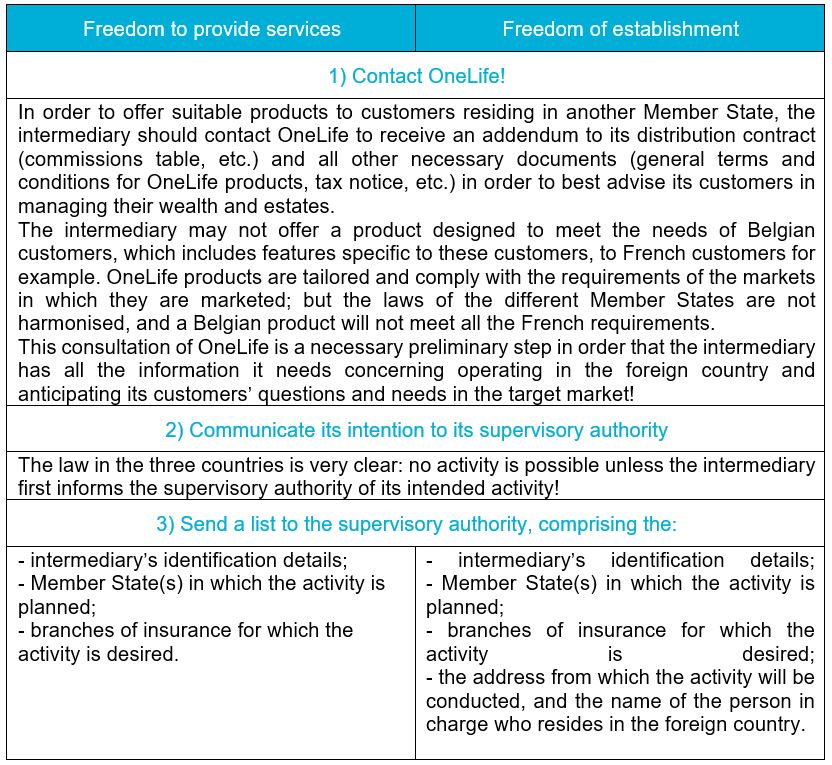

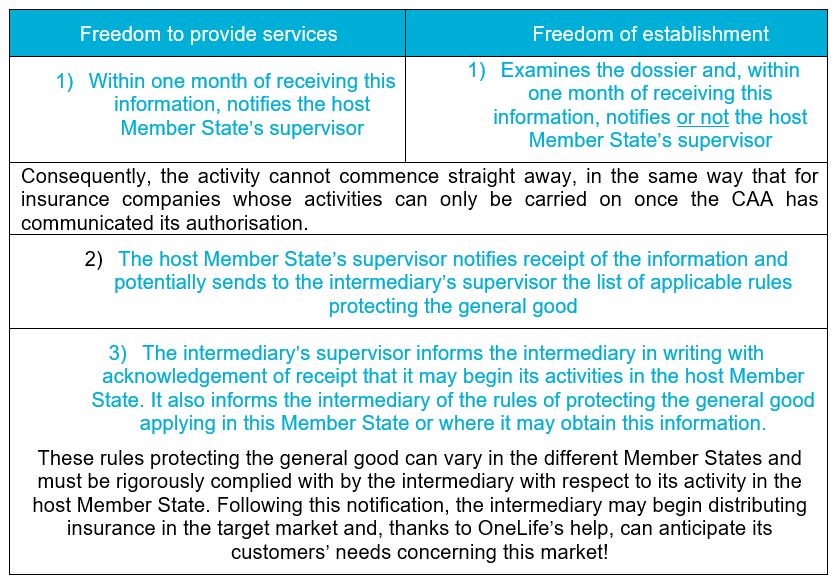

1. Freedom to provide services

1. Freedom to provide services

1. The signature by France and Belgium of a Convention preventing double taxation of successions

1. The signature by France and Belgium of a Convention preventing double taxation of successions